|

v0.14.0 |

|

v0.14.0 |

We will start this tutorial by introducing the idea of the mixed form and its difference from the coupled problem formulation. In case of the coupled problem, we consider the interplay between two (or more) sub-problems governed by different physical equations and therefore described by two (or more) fields. Examples of coupled problems include thermoelasticity, electroelasticity, fluid-structure interaction and many others. On the contrary, mixed problem formulation is obtained upon introduction of one (or more) auxiliary variable(s) in a problem governed by one physical process. Examples of classical problems permitting (and benefiting from) such formulation are:

There are multiple reasons for using mixed formulation, see [14] for more details:

Note that in this tutorial particular attention will be given to the error estimators naturally emerging within the mixed formulation and permitting easy implementation of adaptive refinement.

The strong form of the boundary value problem for the Poisson equation reads:

\[ \begin{align} \label{eq:poisson}-\textrm{div}\:(\nabla u) = f & \quad \textrm{in}\; \Omega \\ \label{eq:dirichlet}u = 0 & \quad \textrm{on}\; \partial\Omega, \end{align} \]

where the homogeneous Dirichlet boundary condition is imposed on the whole boundary of the domain. In order to obtain the mixed formulation, we introduce a new variable \(\mathbf{q}\) representing the flux and rewrite the statement of the problem as follows:

\[ \begin{align} \label{eq:flux}\mathbf{q} &= \nabla u & \textrm{in}\; \Omega\\ \label{eq:cont}-\textrm{div}\,\mathbf{q} &= f & \textrm{in}\; \Omega\\ \label{eq:bc}u &= 0 & \textrm{on}\; \partial\Omega. \end{align} \]

We then multiply the left and right hand sides of Eqs. \eqref{eq:flux} and \eqref{eq:cont} by test functions \(\delta\mathbf{q}\) and \(\delta u\), respectively, and integrate over the domain:

\[ \begin{align} \label{eq:flux_int}\int_{\Omega}\mathbf{q}\cdot\delta\mathbf{q}\,\textrm{d}\Omega - \int_{\Omega}\nabla u \cdot \delta\mathbf{q} \,\textrm{d}\Omega &= 0 \\ -\int_{\Omega}\textrm{div}\,\mathbf{q}\delta u \,\textrm{d}\Omega &= \int_{\Omega}f\, \delta u \,\textrm{d}\Omega \end{align} \]

We now notice that the second term in \eqref{eq:flux_int} can be integrated by parts, providing:

\[ \begin{align} \label{eq:flux_int_part}\int_{\Omega}\mathbf{q}\cdot\delta\mathbf{q}\,\textrm{d}\Omega + \int_{\Omega} u\, \textrm{div}\, \delta\mathbf{q} \,\textrm{d}\Omega -\int_{\partial\Omega} u\, \delta\mathbf{q}\cdot\mathbf{n} \,\textrm{d}\Gamma &= 0 \\ -\int_{\Omega}\textrm{div}\,\mathbf{q}\,\delta u \,\textrm{d}\Omega &= \int_{\Omega}f\, \delta u \,\textrm{d}\Omega \end{align} \]

Since \(u=0\) on \(\partial\Omega\), the boundary term in \eqref{eq:flux_int_part} vanishes. Note that in this case the Dirichlet boundary condition on the field \(u\) \eqref{eq:bc} is imposed in the sense of natural boundary condition, which is typical for mixed formulations. We arrive at the mixed weak form of the problem \eqref{eq:poisson}-\eqref{eq:dirichlet}: Find \(\mathbf{q}\in H(\textrm{div};\Omega)\) and \(u\in L^2(\Omega)\) such that

\[ \begin{align} \label{eq:weak_1}\int_{\Omega}\mathbf{q}\cdot\delta\mathbf{q}\,\textrm{d}\Omega + \int_{\Omega} u\, \textrm{div}\, \delta\mathbf{q} \,\textrm{d}\Omega &= 0 & \forall\, \delta\mathbf{q} \in H(\textrm{div};\Omega)\\ \label{eq:weak_2}\int_{\Omega}\textrm{div}\,\mathbf{q}\,\delta u \,\textrm{d}\Omega &= -\int_{\Omega}f\, \delta u \,\textrm{d}\Omega & \forall\, \delta u \in L^2(\Omega) \end{align} \]

where the following notations of function spaces were used:

\[ \begin{align} L^2(\Omega) &:= \left\{ u(\mathbf{x}) : \Omega \rightarrow R \;\left|\; \int_{\Omega}|u|^2\;\textrm{d}\Omega = ||u||^2_{\Omega} < +\infty\right.\right\} \\ H(\textrm{div};\Omega) &:= \left\{ \mathbf{q} \in [L^2(\Omega)]^2 \;\left|\; \textrm{div}\:\mathbf{u}\in L^2(\Omega)\right.\right\} \end{align} \]

As was mentioned above, one of the main benefits of the mixed formulation is associated with embedded error estimates. It is important to distinguish between error indicators which compute local measure of the error and error estimators which provide mathematically strict bounds on the global error. In this tutorial we will consider only the former, and in particular, will study a simple error indicator which represents the norm of difference between the gradient of field \(u\) and the flux \(\mathbf{q}\) computed over a finite element \(\Omega_e\), see [62] for more details:

\[ \begin{equation} \label{eq:indic}\eta_e := ||\nabla u - \mathbf{q}||_{\Omega_e}^2. \end{equation} \]

Note that function MixedPoisson::runProblem() is shorter than in previous tutorials, e.g. SCL-1: Poisson's equation (homogeneous BC) since several functions are nested in MixedPoisson::solveRefineLoop():

Furthermore, function MixedPoisson::readMesh() is similar to the one in SCL-1: Poisson's equation (homogeneous BC) and will not be discussed here. However, the function MixedPoisson::setupProblem() has features unique to the considered problem:

First, we add domain fields for the flux \(\mathbf{q}\) (choosing space HCURL) and for \(u\) (space L2). Space H(curl) in 2D is defined as:

\[ H(\textrm{curl};\Omega) := \left\{ \mathbf{q} \in [L^2(\Omega)]^2 \;\left|\; \textrm{curl}\:\mathbf{u}\in L^2(\Omega)\right.\right\} \]

It is important to note that choosing the H(curl) space for fluxes is not a mistake here. In turns out that in 2D case spaces H(div) and H(curl) are isomorphic, and therefore only base for H(curl) has been implemented in 2D. Base vectors for H(div) space can be easily obtained after rotation of H(curl) space base vectors by a right angle, see [14] for more details. Note also that bases of both H(div) and H(curl) are vectorial, and, therefore, only 1 coefficient per base function is required for vector field \(\mathbf{q}\).

Next, user-defined orders are set for the fields: if \(p\) is the order for the flux \(\mathbf{q}\in H(\textrm{div};\Omega)\), then order for the field \(u\in L^2(\Omega)\) is \((p-1)\) which is required to satisfy the inf-sup (LBB) stability conditions [14]. Finally, since in this tutorial we will discuss the implementation of adaptive p-refinement, the user-defined approximation order \(p\) is stored in the MOAB database on tags of each domain element.

Setting the integration rule in function MixedPoisson::setIntegrationRules() is similar to other tutorials:

The highest order of the integrand is found in the diagonal term in Eq. \eqref{eq:weak_1}, and therefore the rule is set to \((2 p + 1)\), where \(p\) is order of base functions for fluxes. Note that the order is increased by 1 to accommodate for the case of the higher order geometry.

As was mentioned above, functions MixedPoisson::assembleSystem(), MixedPoisson::solveSystem(), MixedPoisson::checkError() and MixedPoisson::outputResults() are nested in MixedPoisson::solveRefineLoop(). Note that first, these functions are called outside the loop:

If user-defined number of p-refinement iterations is greater or equal to 1, then the loop starts from the refinement procedure and, subsequently, calls to MixedPoisson::assembleSystem(), MixedPoisson::solveSystem(), MixedPoisson::checkError() and MixedPoisson::outputResults() are repeated. We will now consider these functions in more detail.

Assembly of the system requires first computation of the Jacobian matrix, its inverse and the determinant. Furthermore, as the H(curl) space was chosen for approximation of the flux field, the transformation of the base to H(div) space (rotation by the right angle of the base vectors) is obtained by pushing the corresponding operator. Moreover, as the base for H(div) space is vectorial, the contravariant Piola transform is required, see [14] for more details, and the associated operator is also pushed to the pipeline. Upon these preliminary steps, only three additional operators are needed to assemble the discretized version of the system \eqref{eq:weak_1}- \eqref{eq:weak_2}:

The solution of the system is implemented in MixedPoisson::solveSystem() and is similar to other tutorials. However, function MixedPoisson::checkError() deserves discussion here:

First, computation of the error and error indicators requires the same operators for Jacobian (inverse and determinant), transformation of the base for the space H(div) and contravariant Piola transform as were discussed above. Upon pushing those, we add operators for evaluating values of the field \(u\), its gradient, and the values of the flux \(\mathbf{q}\) at gauss points of the domain elements. Finally, before the loop over all finite elements is performed, the operator MixedPoisson::OpError() is pushed to the pipeline:

In particular, operator MixedPoisson::OpError integrates over the domain elements following values:

These values are then stored as tags on the corresponding elements in the MOAB database, and, furthermore, are summed up with contributions from other elements to provide the global values.

What remains to be discussed is probably the most important part of this tutorial: how the computed values of the error indicator are used to drive adaptive p-refinement. The corresponding algorithm is implemented in MixedPoisson::refineOrder():

The algorithm starts by looping over all domain elements and reading the current approximation order and the value of the error indicator from tags of the MOAB database. If for a given element the local indicator is greater than the mean value over the whole domain, i.e.

\[ \begin{equation} \label{eq:crit}\eta_e>\frac{1}{N}\sum_{e=1}^{N}\eta_e, \end{equation} \]

where \(N\) is total number of domain elements, then such element is added to the refinement level corresponding to its current approximation order. Once the criterion \eqref{eq:crit} is checked for all elements in the domain, the approximation order \(p\) is increased by 1 only for elements marked for the refinement on the current iteration.

To demonstrate the discussed above implementation of the mixed form, we consider the Poisson equation in the rectangular 2D domain with Dirichlet boundary conditions prescribed on the whole boundary:

\[ \begin{cases} -\textrm{div}\:(\nabla u) = f &\textrm{in}\; \Omega := \left(-\frac{1}{2};\frac{1}{2}\right)\times\left(-\frac{1}{2};\frac{1}{2}\right)\\ u = 0 &\textrm{on}\; \partial\Omega \end{cases} \]

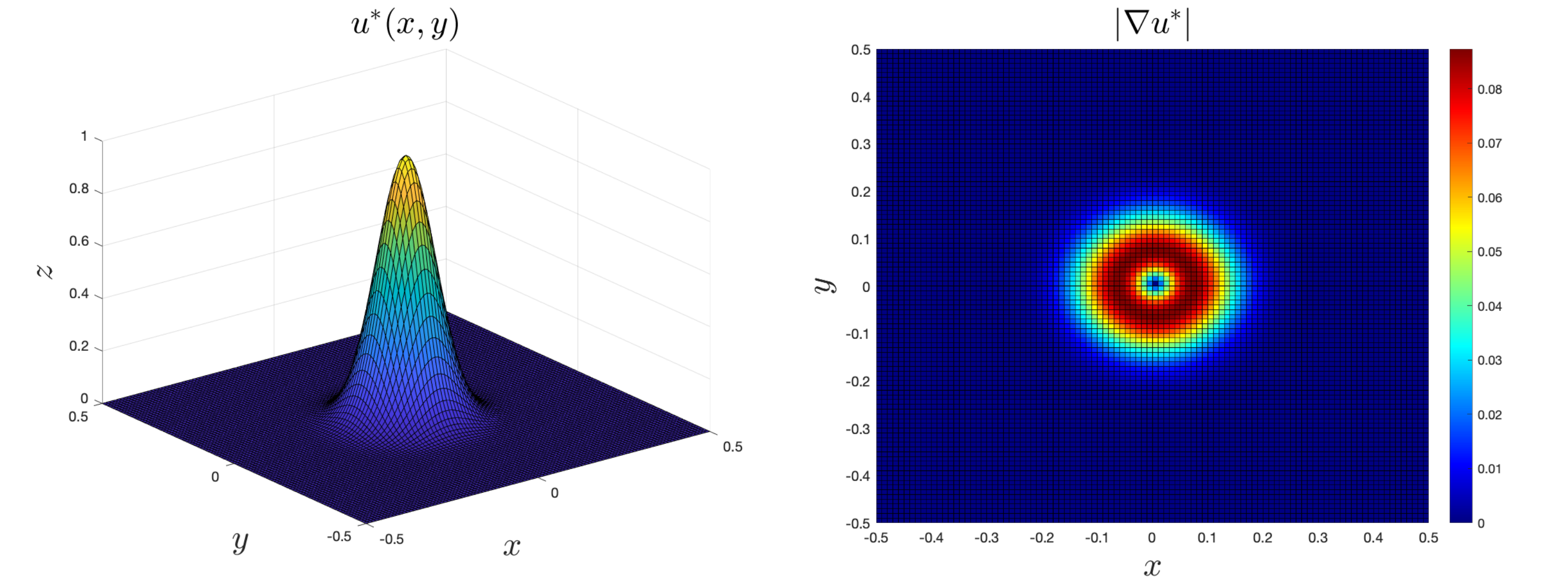

For testing purposes, we will construct the problem for a given solution:

\[ u^*(x,y)= e^{-100(x^2 + y^2)} \cos \pi x \cos \pi y \]

The gradient of this functions is

\[ \nabla u^* = \begin{bmatrix} -e^{-100(x^2 + y^2)} (200 x \cos\pi x + \pi \sin\pi x) \cos\pi y\\ -e^{-100(x^2 + y^2)} (200 y \cos\pi y + \pi \sin\pi y) \cos\pi x \end{bmatrix}, \]

see Figure 1, while the source term reads:

\[ f(x,y) = -e^{-100(x^2 + y^2)} \Bigl\{400 \pi (x \cos\pi y \sin\pi x + y \cos\pi x \sin \pi y) +2\left[20000 (x^2 + y^2) - 200 - \pi^2 \right]\cos\pi x \cos\pi y \Bigr\} \]

First, we will verify the implementation by running the code without the refinement loop:

Using meshes with different element sizes and setting different approximation orders, we can study the convergence of e.g. field \(u\), see Figure 2(a), which for the considered mixed formulation satisfies the following a priori error bound, see [14]

\[ ||u^h-u^*||_{\Omega}\leq C(u,\mathbf{q})\,h^{p} \]

where \(h\) is the element size, \(p\) is approximation order for fluxes field \(\mathbf{q}\) and order for field \(u\) is \((p-1)\).

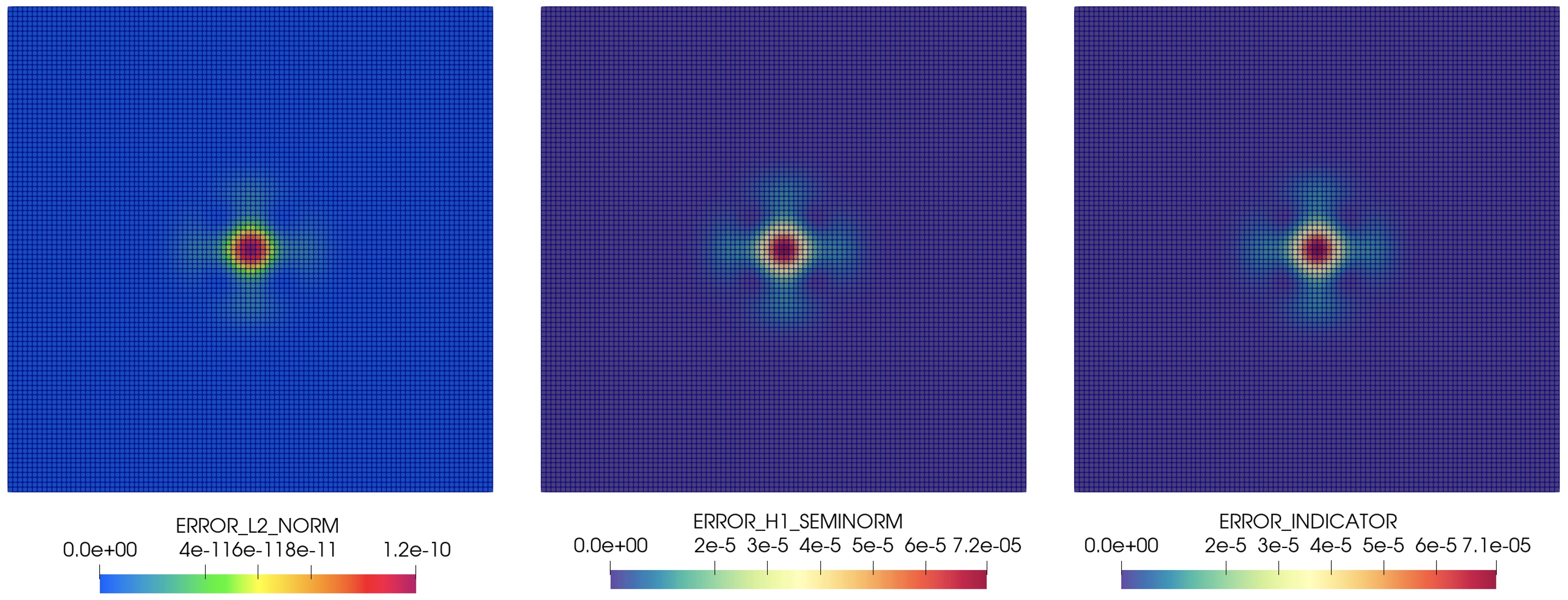

Furthermore, we can plot the values of the local errors and local error indicators \(\eta_e\), given by \eqref{eq:indic}. Figure 3 shows that the considered error indicator (difference between the gradient of field u and the flux) is very close to the H1 seminorm of the error computed using the analytical solution. Moreover, the indicator is very effective in highlighting the regions where the L2-norm of the solution is pronounced.

Next, we run the code invoking the adaptive p-refinement:

In this case, we can observe coherent evolution of the approximation orders saved on element tags and the corresponding distribution of the error in the domain, see Figure 4:

Finally we extend the convergence analysis and plot the error as a function of number of DOFs used in simulation, see Figure 2(b). We can observe in this simple example the effectiveness of using the p-adaptivity, driven by the error indicator. Indeed, such an approach, which is increasing approximation order only in regions where the error is pronounced, requires much less DOFs then the approach based on global h- or p-refinement to obtain the same accuracy of the solution.