|

v0.14.0 |

|

v0.14.0 |

Navier-Stokes equations (NSE), governing the motion of a viscous fluid, are used in various applications: from simulations of the flow in blood vessels to studies of the air flow around aeroplane wings and rotor blades, scaling up to models of ocean and atmospheric currents. Even in the case of an incompressible steady flow, NSE are non-linear due to the effect of the inertia, which is more pronounced in case of a higher Reynolds number. In this tutorial we discuss the implementation of a viscous fluid model in MoFEM using hierarchical basis functions. This approach permits us to locally increase the order of approximation, enforcing conformity across finite element boundaries, without the need to change the implementation of an element. Moreover, the requirement of different approximation orders for primal (velocity) and dual (pressure) variables, necessary for a simulation of the flow using the mixed formulation, can be easily satisfied.

An incompressible isoviscous steady-state flow in a domain \(\Omega\) is governed by the following equations:

\[ \begin{align} \label{eq:balance_momentum} \rho \left(\mathbf{u}\cdot\nabla\right)\mathbf{u} - \mu\nabla^2\mathbf{u} + \nabla p &= \mathbf{f},\\ \label{eq:cont} \nabla\cdot\mathbf{u} &= 0, \end{align} \]

where \eqref{eq:balance_momentum} is the set of Navier-Stokes equations, representing the balance of the momentum, and \eqref{eq:cont} is the continuity equation; \(\mathbf{u}=[u_x, u_y, u_z]^\intercal\) is the velocity field, \(p\) is the hydrostatic pressure field, \(\rho\) is the fluid mass density, \(\mu\) is fluid viscosity and $\mathbf{f}$ is the density of external forces. The boundary value problem complements the above equations by the Dirichlet and Neumann conditions on the boundary \(\partial\Omega\):

\[ \begin{align} \label{eq:bc_d}\mathbf{u} = \mathbf{u}_D & \;\text{on}\; \Gamma_D,\\ \label{eq:bc_n}\mathbf{n}\cdot \left[-p\mathbf{I}+\mu\left(\nabla\mathbf{u} + \nabla\mathbf{u}^\intercal\right)\right] = \mathbf{g}_N & \;\text{on} \;\Gamma_N, \end{align} \]

where \(\mathbf{u}_D\) is the prescribed velocity on the part of the boundary \(\Gamma_D\subset\partial\Omega\), and \(\mathbf{g}_N\) is the prescribed traction vector on the part of the boundary \(\Gamma_N\subset\partial\Omega\), \(\mathbf{n}\) is an outward normal.

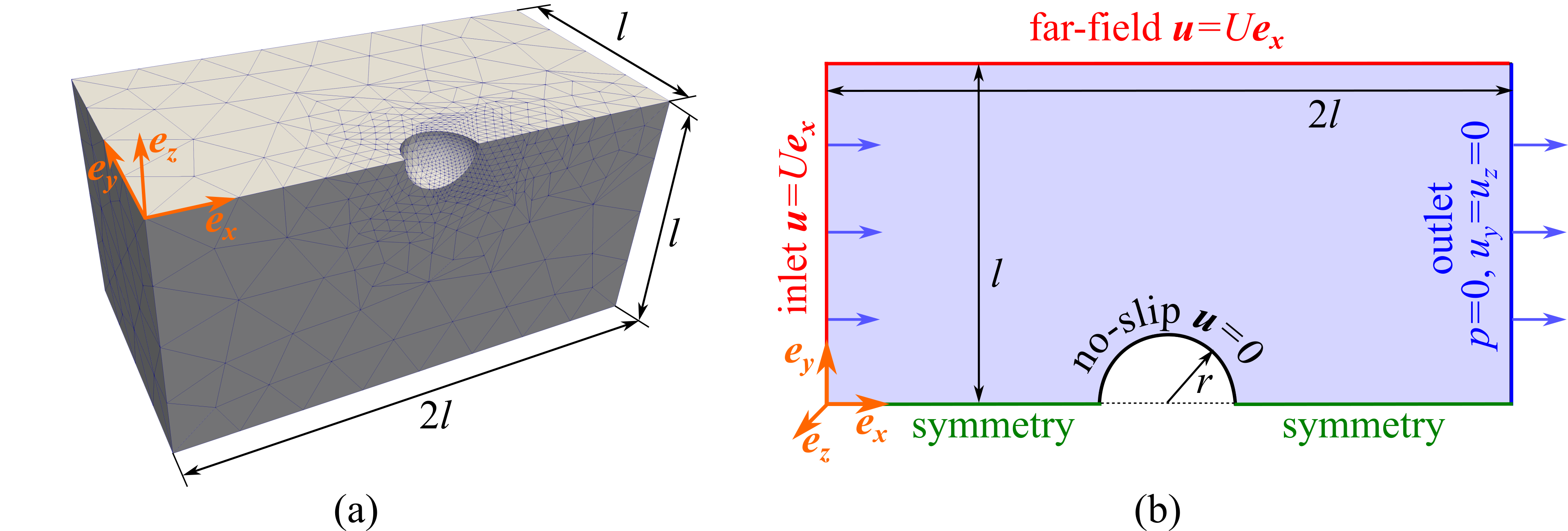

In this tutorial we will solve the problem of the fluid flow around a rigid sphere (see Figure 1) of a radius \(r\) positioned in the centre of a cubic domain, the side length \(2l\) of which is considered sufficiently large compared to \(r\), so that a uniform far-field velocity on the exterior boundaries is valid (note that the body forces are neglected). Exploiting the symmetry of the problem, we will use a quarter of the domain in our simulations.

Note that due to the structure of differential operators in the Navier-Stokes equations \eqref{eq:balance_momentum}, the fluid pressure has to be specified on a part of boundary in order to obtain a unique solution. To achieve that, we will combine Dirichlet and Neumann condition on the outlet boundary of the domain, see see Figure 1. In the case when the flow is perpendicular to the boundary ( \(u_y = u_z = 0\)), which is enforced by the Dirichlet boundary condition, the hydrostatic fluid pressure equals to the normal traction on such boundary, see Theorem 1 in [11].

Reynolds number is introduced for the problems governed by the Navier-Stokes equations as a measure of the ratio of inertial forces to viscous forces:

\[ \begin{equation} \mathcal{R} = \frac{\rho U L }{\mu}, \end{equation} \]

where \(U\) is the scale for the velocity and \(L\) is a relevant length scale. For the problem of the fluid flow around a sphere, considered in this tutorial, the far-field velocity plays the role of the velocity scale, while \(L=2r\), where \(r\) is the radius of the sphere.

When viscous forces dominate over the inertia forces, \(\mathcal{R} \ll 1\), the non-linear term in \eqref{eq:balance_momentum} can be neglected, simplifying NSE down to Stokes equations. However, often this is not the case, i.e. the nonlinear term may become dominant over the viscous forces. In these cases non-dimensionalization (scaling) of Navier-Stokes equations is very useful, which permits to decrease the number of coefficients to only one – Reynolds number \(\mathcal{R}\). The following scales can be used for the case of flow with relatively low Reynolds number (e.g. less than 100).

| Physical quantity | Scale | Dimensionless variable |

|---|---|---|

| Length | \(L\) | \(\mathbf{x}^{*}=\mathbf{x}\:/\:L, \quad \nabla^{*}(\cdot) = L\nabla(\cdot)\) |

| Velocity | \(U\) | \(\mathbf{u}^{*}=\mathbf{u}\:/\:U\) |

| Pressure | \(P=\frac{\mu U}{L}\) | \(p^{*}=p\:/\:P\) |

Mote that the scale for pressure depends on the scales for the length and the velocity. Using these scales, Navier-stokes equations (1) - (2) can be written in the following dimensionless form (considering zero external forces):

\[ \begin{align} \label{eq:balance_momentum_dim_less} \mathcal{R} \left(\mathbf{u}^{*}\cdot\nabla^{*}\right)\mathbf{u}^{*} - (\nabla^{*})^2\mathbf{u}^{*} + \nabla^{*} p^{*} &= 0,\\ \label{eq:cont_dim_less} \nabla^{*}\cdot\mathbf{u}^{*} &= 0, \end{align} \]

Note that now the influence of the non-linearity (inertia terms) on the problem is fully controlled by the value of the Reynolds number. On the one hand, if \(\mathcal{R} \ll 1\), or if one simply wants to consider the Stokes equation, the nonlinear term can be dropped. On the other hand, if the Reynolds number is sufficiently high, then the non-linearity can become strong and may pose problems for convergence (see below discussion of the linearisation of the problem for the Newton-Raphson method). In this case a certain iterative procedure can be used to obtain a solution. Indeed, to find the solution for a given Reynolds number, a number of intermediate problems can be solved for range of smaller \(\mathcal{R}\), eventually reaching the original value. Such technique will also be used in this tutorial. Note also that below we will drop the * symbol, implying that during computation all considered quantities are dimensionless, and a transformation to the dimensional variables is performed before post-processing of the results takes place.

The weak statement of the problem \eqref{eq:balance_momentum}-\eqref{eq:bc_n} reads: Find a vector field \(\mathbf{u} \in \mathbf{H}^1(\Omega)\) and a scalar field \(p \in L^2(\Omega)\), such that for any test functions \(\mathbf{v} \in \mathbf{H}^1_0(\Omega)\) and \(q \in L^2(\Omega)\):

\[ \begin{align} \label{eq:weak} \mathcal{R}\int\limits_\Omega \left(\mathbf{u}\cdot\nabla\right)\mathbf{u} \cdot\mathbf{v} \,d\Omega + \int\limits_{\Omega}\nabla\mathbf{u}\mathbin{:}\nabla\mathbf{v}\, d\Omega - \int\limits_{\Omega}p\, \nabla\cdot\mathbf{v} \, d\Omega &= \int\limits_{\Omega}\mathbf{f}\cdot\mathbf{v}\,d\Omega + \int\limits_{\Gamma_N}\mathbf{g}_N\cdot\mathbf{v}\,d\Gamma_N,\\ - \int\limits_{\Omega}q\, \nabla\cdot\mathbf{u} \, d\Omega &= 0 \end{align} \]

Upon finite-element discretization of the domain \(\Omega\), we consider interpolation of both unknown fields introducing shape functions on each element: \begin{equation} \label{eq:shape} u_i = \sum\limits_{\alpha=1}^{n_{\mathbf{u}}} N_{\alpha}\, u_i^\alpha, \quad p = \sum\limits_{\beta=1}^{n_p} \Phi_{\beta}\, p^\beta; \quad v_i = \sum\limits_{\alpha=1}^{n_{\mathbf{u}}} N_{\alpha}\, v_i^\alpha, \quad q = \sum\limits_{\beta=1}^{n_p} \Phi_{\beta}\, q^\beta, \end{equation} where \(n_{\mathbf{u}}\) is the number of shape functions associated with the velocity field, and $n_p$ is the similar number for the pressure field. Using the hierarchical basis approximation, the vector of the shape functions can be decomposed into four sub-vectors, consisting of shape functions associated with element's entities: vertices, edges, faces and the volume of the element, e.g. for the velocity field:

\[ \begin{equation} \label{eq:shape_hier} \mathbf{N}^\textit{el} = \left[N_1, \ldots N_\alpha, \ldots N_{n_{\mathbf{u}}}\right]^\intercal = \left[\mathbf{N}^\textit{ver}, \mathbf{N}^\textit{edge}, \mathbf{N}^\textit{face}, \mathbf{N}^\textit{vol}\right]^\intercal. \end{equation} \]

Note that in the weak statement velocity and pressure fields belong to different spaces: \(H^1\) and \(L^2\), respectively. Two different approaches can be used for implementing such mixed formulation in the finite-element framework. One can use generalised Taylor-Hood elements, which feature continuous ( \(H^1\) ) approximation of both velocity and pressure fields, however, in order to enforce stability, the approximations functions for the pressure field should be one order lower than those for the velocity field. Furthermore, Taylor-Hood elements impose certain constraints on the mesh, see [77]. Alternatively, a discontinuous approximation for pressure can be used, however, in this case the difference between the orders of approximation functions for velocity and for pressure should be 2.

The example class has necessary fields to store input parameters and internal data structures, as well as a set of functions for setting up and solving the problem:

The set of functions used in this tutorials in the following:

The function ExampleNavierStokes::runProblem is executed from the main function:

The workflow of solving a problem using the finite-element method starts from reading the mesh and other input parameters:

Once the mesh is read, we find the set of tetrahedra corresponding to the computational domain. Furthermore, we identify the fluid-structure interface, i.e. the set of triangles corresponding to the surface of the sphere:

Once the domain and the fluid-structure interface are identified, we can setup the problem. First, we define the velocity and pressure fields. Note that for velocity we use space H1, while for pressure the user can choose between using also H1 space (continuous approximation, Taylor-Hood element), or a discontinuous approximation using L2 space. Note that in the former case, the approximation functions for pressure has to be one order lower than that of the velocity (e.g. order 2 for velocity and order 1 for pressure), while the the latter case the difference between the two has to be 2 orders (e.g. order 3 for velocity and order 1 for pressure).

Furthermore, the properties of hierarchical basis functions can be used to locally increase the approximation order for the elements on the fluid-structure interface, where the gradients of the velocity can be expected to be the highest due to the no-slip boundary condition on the surface of the sphere.

After that the finite elements operating on the set above fields can be defined. In particular, we define elements for solving Navier-Stokes equations, computation of the drag traction and force on the surface of the surface, and, finally, for computing the contribution of Neumann (natural) boundary conditions.

Once the finite elements are defined, we will need to create element instances and push necessary operators to their pipelines. First, we setup an element for solving Navier-Stokes (or if one prefers, Stokes) equations. Note that right-hand side and left-hand side elements are considered separately. In case of Navier-Stokes equations, operators are pushed to elements pipelines using function NavierStokesElement::setNavierStokesOperators. In particular, the following operators are pushed to right-hand side:

while for the left-hand side we push these operators:

Upon that, we setup in the same way elements for computing the drag traction and the drag force acting on the sphere using operators NavierStokesElement::OpCalcDragTraction and NavierStokesElement::OpCalcDragForce, respectively. Additionally, operators for the Neumann boundary conditions are set using the function MetaNeumannForces::setMomentumFluxOperators and the element for the Dirichlet boundary conditions is created as well. Finally, operators for post-processing output are created: in the volume and on the fluid-solid interface.

Note that the class for enforcing Dirichlet boundary conditions DirichletDisplacementBc used in the snippet above requires the algebraic data structures for storing components of the right-hand side vector, left-hand side matrix and the solution vector. Therefore, these data structures need to be created beforehand using PETSc:

However, one may note that creation of PETSCc vectors and matrices requires the instance of the MoFEM Discrete Manager (DM), which needs a certain setup as well:

Finally, the last preparatory step required is the setup of the SNES functionality:

We will consider two cases: first, flow governed by Stokes equation, i.e. neglecting the nonlinear terms, and then we will solve full set Navier-Stokes equations. For both cases we will use the same mesh. We will start by partitioning this mesh:

while mofem_part can be found in $HOME/mofem_install/um/build_release/tools/. Here we partitioned the mesh in 4 parts in order to be executed on 4 cores in a distributed-memory parallel environment. Note that any number of parts less or equal to number of physically available cores can be used.